An Observation of Producing Efficiently Without Producing Too Much

In Lean Six Sigma, much time and analysis has been devoted to identifying production hiccups or “speed bumps” that disrupt the smooth flow of a process. Every smart business aims to minimize wasted time and resources and, therefore, should know common types of interruptions that lead to waste. We will briefly review eight common types of speed bumps and then narrow in on overproduction.

Lean Six Sigma Speed Bumps

There are eight emphasized speed bumps in Lean Six Sigma that are outlined using a related acronym, D.O.W.N.T.I.M.E.

Defects

Overproduction

Waiting

Non-Utilized Talent

Transportation

Inventory

Motion

Extra-Processing

Defects: Errors in processing, such as product defects, that require resources and reworking to correct.

Overproduction: Producing more product than is necessary to meet demand.

Waiting: Delays while waiting for another production phase to be completed in order to proceed.

Non-Utilized Talent: Not engaging full potential of employees and their skillsets.

Transportation: Delays in transportation of items or information required to proceed with production.

Inventory: Inventory sitting idle and not being processed.

Motion: People, information, or equipment making unnecessary motion due to poor workspace layout and/or poor system designs.

Extra Processing: Activities not necessary for production of a finished product or service.

Again, our focus in this article is on overproduction. This is the production of more product than is necessary to meet demand.

Inventory vs. Demand

As for meeting demand, some may assume that to produce only product necessary to meet demand means that a business should produce only the number of units ordered (literal demand). For example, one might assume that a television manufacturer should only build 3,180 televisions if 3,180 televisions were ordered. This is obviously not how the world works. Stores carry inventory on shelves and in warehouses. Product needs to be available for customers to make instant purchases.

A grocery store will gather data on what products are popular at what time of year and stock their inventory accordingly. Ice cream sales go up in the hot months, and so more might be stocked during those months than in winter. A clothing manufacturer will produce more winter coats in the months leading up to fall and winter than it does in the spring and middle of summer. Producing to meet demand is based on standard (or expected) demand rather than literal demand. On the other hand, some manufacturers will produce certain products on an order-by-order basis, such as a custom vehicle.

Push vs. Pull

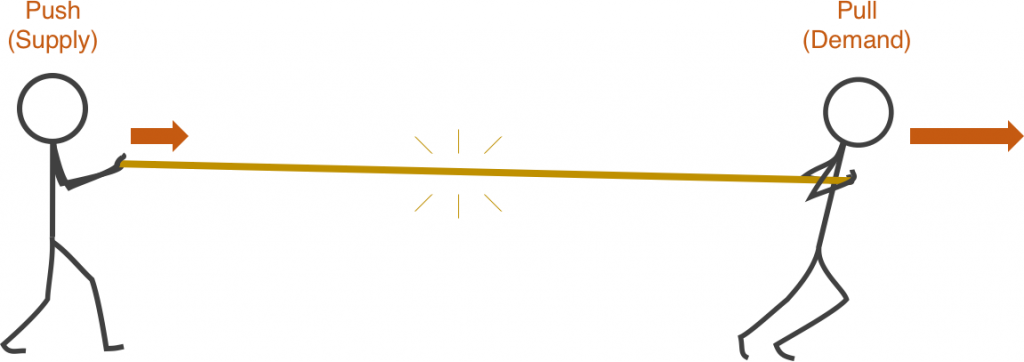

A simple way to visualize supply and demand balance is a rope. On one end (the left), someone pushes the rope. On the other (the right), someone pulls the rope in the same direction. The person pushing represents supply and production; the person pulling represents demand and customer orders:

Each time a customer orders product–such as an order for a television, purchase of a car, etc, this creates a pull event. Each time a manufacturer produces product to meet demand, it creates a push event. The manufacturer’s push (supply) should be quick enough to meet the customer pull (demand).

Underproduction

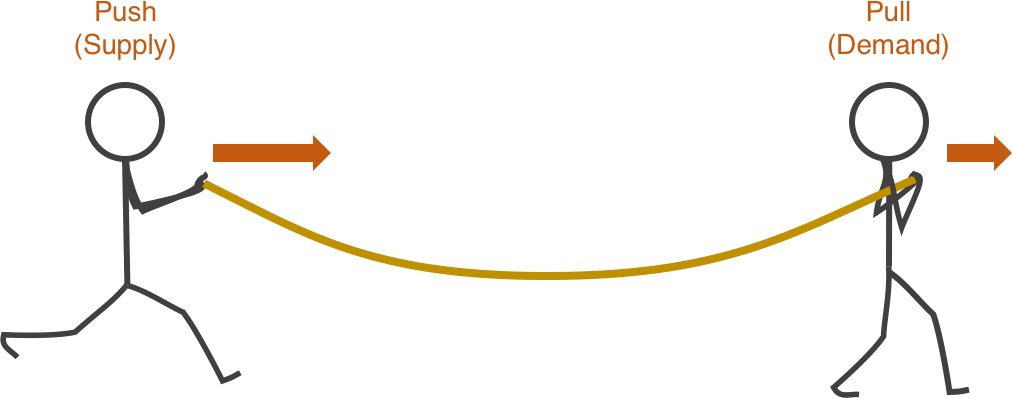

If production is too slow–in other words, customers (individuals or businesses) are ordering more than the manufacturer is producing, this creates frustrating yanking on the rope by customers as they become impatient waiting for their product:

This is underproduction. If the customers are businesses looking to fill their warehouses, they could potentially lose business as their retail customers go elsewhere to get faster service.

Overproduction

On the contrary, if the manufacturer creates too much push–or produces more product that is necessary to meet standard demand, this creates slack in the rope:

This is overproduction–when a manufacturer produces too much product. They produce product, in other words, before it is ready to be purchased. Overproduction is usually evidenced by too much product sitting idle in warehouses and on retail shelves and not being moved for long periods of time. Much of the time, product is not sold at all, resulting in even more waste.

Waste due to overproduction occurs in the form of foregone profits when the manufacturer or business customers must sell their product at clearance prices, in wasted staff time as they must strategize on how to deal with excess and unsold inventory, in additional staff time to execute setup of sales and clearance shelves, in lost production time and staff is pulled away from standard tasks, and other wasted resources.

In Closing

In short, it is important to take the time to analyze what product is needed and in what quantities. To get it right, it takes time and study of actual sales and seasonal fluctuations in business–and, of course, trial and error. Minimizing overproduction will be well worth your time and worth it to your work space.