Thoughts on preparing for the turbulence that comes with business.

Any business making legitimate strides toward a positive goal is moving in some direction, and any business that is moving is naturally going to face obstacles and bumps in the road. These bumps in the road range from day-to-day variances to unique, major variances that sway a business away from its primary goal of producing a product or service in a consistent and timely manner. Identifying and defining both common and infrequent obstacles is a critical part of business success and survival.

In this article, we will focus primarily on day-to-day, expected variations in productivity. In the Six Sigma system of process improvement, these are called common cause variations. To help bring understanding to the differentiation, let’s look at a couple of important definitions.

Six Sigma: Primary Types of Variation

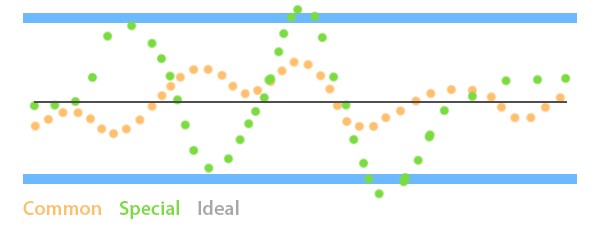

In the Six Sigma system of process improvement, two primary types of variations from ideal (or average) productivity are defined:

Day-to-day, hour-by-hour variations due to common, daily activities. These variations are unavoidable and built into the process.

- Special Cause Variations

One-time or infrequent variations caused by rare circumstances, such as disasters. These variations are typically not foreseeable and need corrective action.

The Gravel Road

To illustrate the overall picture, we’ll use the example of a car driving down a gravel road:

When you drive down a gravel road, you have a feeling of movement. You know the car is headed where you want to go, despite the somewhat rough ride. In the end, the car is moving in the right direction. Small bits of gravel that cover the road and over which the car rolls do create a constant bumpy ride, but it is bearable. There is no need for oversteering or constant braking to respond to each bit of gravel.

The gravel is your constant, expected turbulence–your common cause variation–that is minor enough to continue forward without disrupting the trip.

Special cause variation, on the other hand, would be like large rocks and potholes that you come across occasionally on the road. To avoid these, substantial steering, swerving, and/or braking is necessary to safely navigate. If one of these is struck, it’s possible that extra steering will be necessary to recover the vehicle’s normal trajectory. These larger obstacles do not pop up often, but it is good to be ready when they do.

Examples

What do these variances look like in the business world? It helps to first observe that no business is perfect. The result is that there must be some level of standard variation from ideal productivity that is deemed acceptable.

Common Cause Variation

For example, take a ridesharing service like Uber or Lyft. Riders request many rides in concentrated cities where there are plenty of drivers present to make quick pickups the norm. Let’s say the organization aims for a standard wait time between a rider requesting a ride and a driver arriving for pickup of four minutes. In reality, drivers arrive in three to seven minutes on average. This is because there are stoplights, traffic, pedestrians, weather conditions, and other common obstacles that lie between the driver and the rider–and the amount of delay they cause varies constantly. There is no need to respond to these common delays because these delays are built into the process.

Special Cause Variation

Now consider that a sinkhole occurs in the middle of a main intersection and shuts it down. This causes major delays and backups for everyone, bringing the average wait time for riders to sixteen minutes. This is a major disruption and one that should be responded to with best-case alternative strategy.

How Should Organizations Respond to Variations?

In day-to-day business, there are some occasional issues that warrant a major corrective response and others that do not. We alluded to this in our prior example, pointing out that major response to normal traffic in a city is not needed; it is normal. A disruptive sinkhole does require alternative strategy.

Our focus here is the common. Other examples of common cause variation are a printer running out of paper, an assembly line arm needed to pause for regular maintenance, or a freight truck needing an oil change. These things can cause small variations in production time, but they are expected and planned for. They are not a surprise. An organization does not need to hold a conference call to decide how to respond to an empty printer. A worker pauses, grabs another ream, and pops it in. Back to business.

One other note is that variations can also be positive, warranting a good change in process. But that is a topic for the special variance section.

Prep, Not Avoidance

One might think that a major key to business success is avoiding trouble altogether. However, consider this simple law of physics: Every moving object faces a level of resistance. All the same, any time we are moving–whether it be toward our personal goals or business goals–there will be problems in our way that we must decide how to handle.

The issue at hand is not how to avoid all trouble, but how to respond to it and what to respond to. The key Six Sigma categories of common cause variation and special cause variation are helpful aids in planning how your organization will conserve time and material resources by responding